Navigation

A cryogenic seed bank for preservation of endangered plant species

By training, Harold Koopowitz is a neurobiologist, someone who studies the brains and nervous systems of animals. As a child, he collected wildflowers in his native South Africa, and he continued his hobby when he moved to the United States to pursue his profession. When he learned about the high rates of endangerment and extinction faces by plants, he decided to devote some of his scientific ingenuity to their protection. Today, Koopowitz directs the arboretum at the University of California at Irvine. One component of the arboretum’s activities is a cryogenic seed bank.

Location:

University of California, Irvine CA, United States of America

Problem Overview:

Rapid rate of plant extinction, loss of genetic diversity

When we think of saving endangered species from severe population loss or even from extinction, we usually think of endangered animals – birds such as the whooping crane, mammals such as the giant panda, or reptiles such as the crocodile. Yet many species of plants face an endangered and embattled existence as well.

When we consider the benefits we derive from plants, it is clear that their needs for survival merit our attention, too. Humans are among the many species whose food chain begins with plants. We consume food in order to provide energy for our bodies. But the amount of energy in the universe is finite; quite simply, in order for us to use it, we need to get it from somewhere else.

Like most other creatures on earth, we depend on energy captured from the sun’s rays. Most of the energy we get this way comes to us by way of plants. They capture it in the process of photosynthesis and use it to grow. We then meet our energy needs, along with our nutritional requirements, from the plants, either directly, when we eat the plants, or indirectly, when we consume animals who themselves have plants at the beginning of their food chains.

Of course, plants give us much more than energy and nutrition. They play a large role in regulating and maintaining the temperature and the liquid and gas makeup of the atmosphere. By absorbing water and by holding soils in place they prevent flooding. They provide natural beauty, materials for shelter and clothing, and components of soaps, oils, resins, and cosmetics we use every day. One-fourth of all prescription drugs come from plants – some from quite rare and endangered ones.

Plants now go extinct at a rate of two to three species per day. Many more are in danger of extinction, and the rate is likely to go up as human activities take their toll on the plants’ natural habitats. Even when a species survives, the loss of even part of its natural habitat means that it has fewer defenses against pests, diseases, and environmental changes (such as in the temperature, or the amount of sunlight or water available) for the future. In the course of evolution, plants, like all living things, draw on their range of genetic resources – on the variety of different individuals in the species with different strengths and weaknesses – in order to meet new challenges in their environments. The less there is of such genetic diversity, the more likely the species is to face endangerment or even extinction.

There are many reasons to protect endangered plants and their habitats. Even for food plants found widely throughout the world, rare strains exist that hold the genetic keys to healthier and more nutritious varieties.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to save plant species is to give us time to learn what we can do about their medical and other properties. Plants are efficient and creative factories of new chemicals; because these chemicals have evolved in order to protect the plant from environmental insult, they often turn out to be of use to humans as well. Several of the most important drugs used in cancer and leukemia therapies today come from rare species of plants found only in small corners of the world. But identifying and testing plant chemicals is a slow and painstaking process. Saving endangered plants provides us with the opportunity to investigate them, and therefore with the chance to feed more people and to conquer more disease.

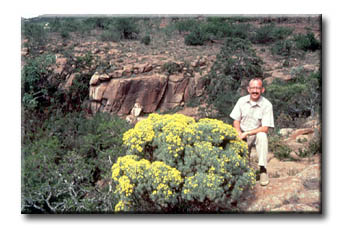

By training, Harold Koopowitz is a neurobiologist, someone who studies the brains and nervous systems of animals. As a child, he collected wildflowers in his native South Africa, and he continued his hobby when he moved to the United States to pursue his profession. When he learned about the high rates of endangerment and extinction faces by plants, he decided to devote some of his scientific ingenuity to their protection. Today, Koopowitz directs the arboretum at the University of California at Irvine. One component of the arboretum’s activities is a cryogenic seed bank.

|

| Dr. Harold Koopowitz, featured in One Second Before Sunrise I with his work with cryogenic storage of endangered seeds, a preservation method to protect the seeds until their native habitat can be protected. He is seen here in South Africa |

A gene bank is what scientists call any effort to conserve genetic diversity, in order either to keep species from becoming endangered or extinct, or to preserve the variety within a species. For both plants and animals, the ideal gene bank is a natural habitat that is protected from destruction. This kind of protection is said to be "in situ" – meaning that it takes place within the species native habitats. Many people around the world are committed to in situ conservation, but their efforts are not always entirely successful. So, other devote themselves to "ex situ" efforts – protection outside the species’ native habitats.

For plants, the best ex situ gene bank is an arboretum or an experimental garden, farm, or forest, in any of which the growing conditions resemble as closely as possible the various species’ natural habitats. Many of the plants that Koopowitz grows in the arboretum he directs are wildflowers whose native habitats are at risk. But even these measures cannot always keep pace with the high rates of endangerment and extinction. They require valuable and expensive open land – land that might otherwise be used for farming, housing, or industry – and their maintenance requires much time and expertise. There is always a risk that the cultivated plants will not survive.

Koopowitz’s cryogenic seed bank is a kind of ex situ gene bank that takes little space and is easy to maintain. It involves, simply enough, collecting and labeling seeds and placing them in a freezer that is kept at minus 40 degrees centigrade. Finding the proper storage conditions and temperature, and testing for the viability of seeds after various periods of time in the freezer, took some time, but the technique is now a proven one. Koopowitz started the first cryogenic seed bank in the United States, and he has since encouraged many others to follow suit. He has also been a leader in convincing other arboreta to expand beyond their traditional role – providing a place for the study of plant species and their growth – and to get more directly involved in the conservation of endangered plant species. While the preservation of natural habitats is still the most important goal, ex situ measures such as these are needed while those habitats remain at risk.

Web Links:

Description | web_address |

The Kew Seed Bank at Wakehurst Place | http://www.rbgkew.org.uk/seedbank/index.html |

Documentation:

Documented in HORIZON International's film "One Second Before Sunrise", Program I

The television program is available for viewing and downloading at http://www.horizoninternationaltv.org/.

Submitted by:

HORIZON

- Login to post comments

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Promoting the Development of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation -Case from Zhejiang Province, China

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Promoting the Development of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation -Case from Zhejiang Province, China

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Water

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Water and Sanitation

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems