Navigation

Alternative Fishing Gear Can Reduce Shark Mortality:Pew lays out simple steps to cut bycatch numbers

A new global scientific review shows that simple changes in fishing gear could significantly reduce the large number of sharks unintentionally caught in the world’s oceans.

A new global scientific review shows that simple changes in fishing gear could significantly reduce the large number of sharks unintentionally caught in the world’s oceans. The paper, “Fisheries Bycatch of Sharks: Options for Mitigation,” released today by the Pew Environment Group, outlines practical options for reducing shark injury and death from commercial fishing, a leading cause of shark population decline.

|

Although sharks are not the primary target of most fisheries, they can make up the majority of the catch in some regions of the world. Pew’s Ocean Science Division worked with two scientific experts to research options to reduce shark bycatch, which occurs when the animals are caught in fishing gear set for other species.

|

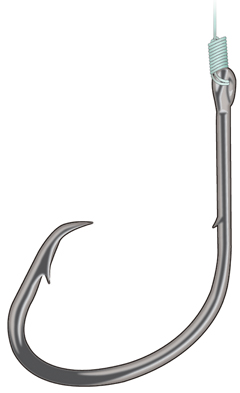

| J hooks commonly used in fisheries, can be replaced by circle hooks. The impact of using circle hooks to reduce shark bycatch has been variable. Text from the Report. Photograph by Phil Geib courtesy of Pew Environment Group. |

|

| As is the case with sea turtles, circle hooks do appear to decrease mortality of hooked sharks, because most individuals are externally hooked in the mouth or jaws, in contrast with J and tuna hooks. Photograph by Phil Geib courtesy of Pew Environment Group. |

Viable modifications found by the researchers include changing the type of bait; switching the material used to create leaders, which attach fishing lines to hooks; and modifying the shape of hooks.

Fishermen sometimes use wire leaders to maximize shark catch, but replacing the wire with nylon can allow sharks to break free because they can bite through the line.

“Banning wire leaders and not allowing vessels to retain certain species would help reduce the vast number of sharks caught and killed in Atlantic fisheries,” said Jill Hepp, manager of global shark conservation for the Pew Environment Group. “The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas meeting is a good place to build support for using some of these new methods to avoid catching sharks in the first place.”

|

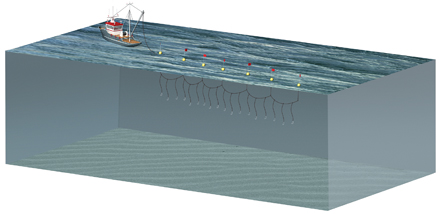

| The scientific review, released at the annual meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) in Istanbul, reports that in the U.S. Atlantic, sharks made up 25 percent of the total catch of the pelagic (open ocean) longline fishery between 1992 and 2003. Image from the Report courtesy of Pew Environment Group |

The scientific review, released at the annual meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) in Istanbul, reports that in the U.S. Atlantic, sharks made up 25 percent of the total catch of the pelagic (open ocean) longline fishery between 1992 and 2003. In 2009, fishing vessels belonging to ICCAT members reported catching 58,100 metric tonnes of blue sharks, 264 metric tonnes of porbeagles, and 5,605 metric tonnes of shortfin makos in the Atlantic.

|

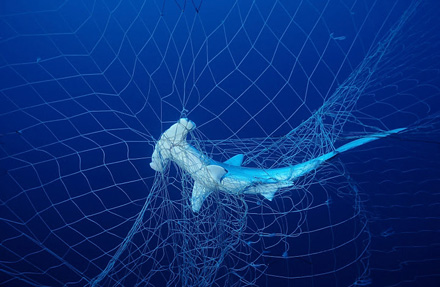

| A hammerhead shark caught in a fishing net. Photograph courtesy of Seawatch.org. |

The convention’s scientific committee says progress has been made in recent years to protect bigeye thresher, oceanic whitetip, and hammerhead sharks in the Atlantic. The committee recommends that silky sharks receive the same level of protection, since these animals were classified in ICCAT’s most recent Ecological Risk Assessment as being among the most vulnerable species.

“While enhanced protections are now helping to safeguard certain species, the majority of sharks remain under threat due to countries’ overall lack of political will to control the amount of bycatch hauled in by their fishing vessels,” Hepp said. “This review spells out clearly that there are plenty of options available to make fishing more sustainable when it comes to sharks, which, coupled with better fisheries management, would go a long way toward protecting these animals.”

|

| Blue shark. Photograph by Karen Leonard, Marine Photobank |

The increasing demand and high prices for shark fins means fishermen have little motivation to release these animals while they are still alive. Up to 73 million sharks are killed every year, primarily to support global demand for fins, which are prized in Asia as a delicacy in soup.

This news is from the Pew Environment Group 15 November 2011.

See related articles on Horizon International’s coral reefs and oceans website www.coralreefs.co and www.magicporthole.org

Notes:

The Pew Environment Group is the conservation arm of The Pew Charitable Trusts, a nongovernmental organization that works globally to establish pragmatic, science-based policies that protect our oceans, preserve our wildlands, and promote clean energy. For more information, visit www.PewEnvironment.org.

· The 22nd regular meeting of ICCAT is taking place Nov. 11-19 in Istanbul. At this year’s meeting, the Pew Environment Group is advocating a ban on retention of porbeagle and silky sharks; establishment of concrete, precautionary catch limits for shortfin mako sharks; and prohibitions on wire leaders and the removal of shark fins at sea.

· The Pew Environment Group also recommends that ICCAT members strengthen controls on illegal fishing of Atlantic bluefin tuna and other species; end overfishing and support sustainable fishing methods; and make ICCAT's charter stronger so that internationally agreed-upon commitments are met.

· Some regional fisheries management organizations require species-specific reporting of shark landings, prohibit finning, seek reductions in fishing mortality, encourage the live release of sharks, or ban the retention of certain species such as threshers, hammerheads, or oceanic whitetip sharks.

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution