Navigation

Living, Meandering River Constructed: Vegetation and sand found to be essential in stream life

In a feat of reverse-engineering, Christian Braudrick of University of California at Berkeley and three coauthors have successfully built and maintained a scale model of a living meandering gravel-bed river in the lab. Their findings point to the importance of vegetation to reinforce the banks and to the importance of sand in healthy meandering river life.

|

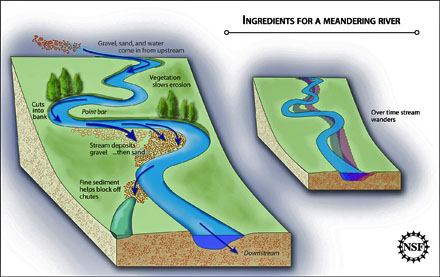

| By reverse-engineering a meandering stream, researchers have shown two ingredients to be very important: vegetation to reinforce banks and prevent erosion, and sand to build point bars and block off cut-off channels and chutes. This knowledge will help stream restoration efforts in the future. Credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation |

In a feat of reverse-engineering, Christian Braudrick of University of California at Berkeley and three coauthors have successfully built and maintained a scale model of a living meandering gravel-bed river in the lab. Their findings point to the importance of vegetation to reinforce the banks and to the importance of sand in healthy meandering river life.

The significance of vegetation for slowing erosion and reinforcing banks has been known for a long time, but this is the first time it has been scientifically demonstrated as a critical component in meandering. Sand is an ingredient generally avoided in stream restoration as it is known to disrupt salmon spawning. However, Braudrick and his colleagues have shown that it is indispensable for helping to build point bars and to block off cut-off channels and chutes--tributaries that might start and detract from the flow and health of the stream.

The model is a first for the delicate balance of ingredients of the model flood plain. Gravel (sand), fine sediment, vegetation and water to come together in such a way that the stream took life and behaved in the way it’s healthy counterparts in nature would at 50 to 100 times the size and on the scale of hours instead of years.

|

| Christian Braudrick and colleagues are the first to build a scaled down meandering stream in the lab that successfully meandered through its flood plain for 130 hours which represents 5 to 7 years of real time in the wild. The substrate seen behind Braudrick is composed of sand to represent real-life gravel; white light-weight plastic for sand, and alfalfa sprouts for deep-rooting vegetation. Credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation |

In 130 hours after being set into motion, this train-set size (6m x 17m) river eroded its banks and built point bars by depositing model sand and gravel moving around in its environment the way parts of the Mississippi River would over five or seven years.

In nature, this behavior not only achieves a "picture perfect" waterway with pleasing bends, but it yields what earth scientist Braudrick calls "more biological bang for the buck."

"Meandering" generally occurs in streams with moderate slopes and is a common form of river between canyon-bound rivers in the mountains and deltas near the ocean. The physics and geology of meandering streams combine to yield both shallow portions as well as deeper pools. The diversity of habitat is a more hospitable environment to sustain a higher diversity of species. This is in contrast to another stream type with many islands but with more uniform and shallower water called "braided streams."

Stream restoration is an extremely complex and delicate science because there is no formula to create meandering streams. Successful stream restorers almost require a sixth sense to get everything right and set a sustainable environment into motion, and not every restored stream lasts. Some form extra channels becoming braided streams; some stagnate.

Braudrick and his colleagues hope to shed light on the necessary conditions for sustained meandering in coarse bedded rivers. They have used a combination of painted sand that stands in for gravel, a light weight plastic that looks like sugar for sand, and alfalfa sprouts that stand in for the deep rooted vegetation, such as cottonwoods or willows that grow along many meandering rivers in the wild.

The research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and appears in the Sept. 28, 2009 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Contact:

Christian Braudrick, University of California, Berkeley

This article is from a National Science Foundation release of September 28, 2009.

Search

Latest articles

Agriculture

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Air Pollution

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Biodiversity

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

Desertification

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- UN Food Systems Summit Receives Over 1,200 Ideas to Help Meet Sustainable Development Goals

Endangered Species

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

- Coral Research in Palau offers a “Glimmer of Hope”

Energy

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Wildlife Preservation in Southeast Nova Scotia

Exhibits

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

- Coral Reefs

Forests

- NASA Satellites Reveal Major Shifts in Global Freshwater Updated June 2020

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Global Climate Change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

- It is time for international mobilization against climate change

Global Health

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- More than 400 schoolgirls, family and teachers rescued from Afghanistan by small coalition

Industry

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

Natural Disaster Relief

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

- Global Innovation Exchange Co-Created by Horizon International, USAID, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Others

News and Special Reports

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- STOP ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE IN UKRAINE

Oceans, Coral Reefs

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Pollution

- Zakaria Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso Produces Film “Nzoue Fiyen: Water Not Drinkable”

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Population

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

Public Health

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Rivers

- World Water Week: Healthy ecosystems essential to human health: from coronavirus to malnutrition Online session Wednesday 24 August 17:00-18:20

- Mangrove Action Project Collaborates to Restore and Preserve Mangrove Ecosystems

Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Toxic Chemicals

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Actions to Prevent Polluted Drinking Water in the United States

Transportation

- "Water and Sanitation-Related Diseases and the Changing Environment: Challenges, Interventions, and Preventive Measures" Volume 2 Is Now Available

- Urbanization Provides Opportunities for Transition to a Green Economy, Says New Report

Waste Management

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

Water and Sanitation

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution

- Honouring the visionary behind India’s sanitation revolution